June 8, 2020

By Jaya Sundaresh

Photos by Tyler A. McNeil

Brandon Brown comes up to me, and there is exhaustion written on his face.

“This is going on longer than it was supposed to,” he tells me. “Half our security team has already gone home.”

Brown is a member of the ad-hoc internal security team the Black Lives Matter protestors have thrown together; last I saw him, he was standing outside the Schenectady police station a week ago, arguing with other protestors who didn’t like the fact that some had chosen to kneel with the police. He tells me to watch out for anyone wearing a gas mask (like the one he wears around his neck, like a trophy) or holding a walkie-talkie. Anyone who looks like they don’t belong.

“We sent home some white militia guys, they said they were there for the same reason we were; to make sure no one got hurt. But they were scaring people, so we sent them home,” says Brown. (It was unclear if this was the same group of militia members apprehended by the Troy police department during the day.)

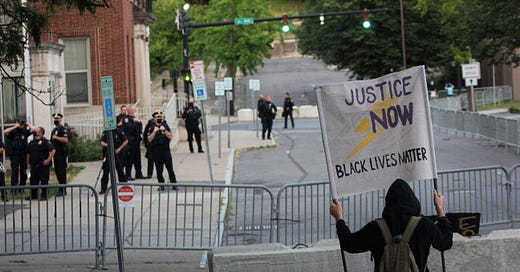

After the main event, after the protest in which 11,000 people in a city of 50,000 marched for peace and justice and love, a small contingent of Trojans held back, Trojans of every hue and gender, holding the line in front of the Troy police department’s headquarters, cheering and shouting and and singing their defiance to the police force that was standing a hundred feet away, arrayed in a line, watching and waiting for something to go wrong.

“We ain’t have to attack nobody! We’re here for the people!” a woman cries into a megaphone, standing on one of the huge cement blocks the police had placed in front of the station. What was meant to be an anti-terrorism measure, a way to prevent vehicles from crashing into the gates, was repurposed as a symbol of strength: a people’s podium.

Sporadic chants of “no justice, no peace, no racist ass police” break out; they gather strength. “I can’t breathe,” starts up again, this time with a tinge of anger that wasn’t there in the daytime. There’s something so powerfully sad and beautiful, I think, about Eric Garner’s last words, George Floyd’s last words, (maybe the last words of Edson Thevenin, who knows,) being thrown back at the police who have threatened these young people their entire lives.

The convivial, family-friendly atmosphere of the day’s march has turned into something more raw, more passionate, and a little more desperate. The sun is setting, and with it, the promise of sun-dappled safety dissipates.

“It’s getting dark, y’all. Group together, remember: there is safety in numbers!” the woman with the megaphone says. She says that Troy PD are cowards, and that anything can provoke them — you don’t want to give them the chance.

The woman with the megaphone addresses those who might not want to stay for the inevitable-seeming confrontation between police and protestors.

“If you don’t feel comfortable staying, you can leave. We will still accept you,” she says, solemnly. You’re still one of us, even if you don’t have the ability to withstand being tear-gassed, even if you can’t manage being kettled and arrested. People, white and Black and brown, surge forward, crying out their support.

Speakers get up to talk into the megaphone, a sort of people’s mic, the kind you’d see at Occupy protests a decade ago.

“People only be robbing because they are poor!” a man says, to huge applause. “People are broke! People are hurt! People are dying!”

Another man gets up, and talks about the necessity for white allies to have “uncomfortable conversations” with their loved ones.

“It’s too easy to cut someone out of your life who you don’t agree with!” he says. Harder to keep them in your life, harder to convince them of the ills of white supremacy and capitalism. But that’s the work that is set out for allies, in this impromptu speech.

The finer points of antiracism were discussed; shouted out; affirmed.

“We are all different! And that’s beautiful! No more of that ‘I don’t see color’ nonsense!” someone says. Difference is what makes us human; and our shared humanity is what makes us similar.

A concert series of sorts is offered: someone plays “Fuck the Police” by N.W.A. on their phone into a megaphone, repeating the song over and over again. The crowd loves it.

It feels like this little world that has been created, with its joy, with its music, it’s knowledge-sharing, even its own internal security team, it feels like it is about to be snuffed out by the police — there are whispers coming through my Signal channels that there are tanks positioned behind the Italian Community Center on 5th Street. The woman with the megaphone says that they heard that the the tanks are up on the hill, by Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. I count at least three helicopters flying low above us, held motionless in the air. I see drones. Rumors abound that the small figures atop the police station are snipers.

It feels like the Paris Commune, it feels like Rojava of Kurdistan, it feels like Zuccotti Park in 2011, it feels like a small flower of democracy blooming in the heart of a police state. For the first time in my life, I feel as if I, even though I’m here as an observer, a reporter, am part of something truly free.

There is disagreement here, of course. No democracy would be complete without its dissidents.

The woman with the megaphone is insistent that the collective extend a negotiator to the police; that we at least hear what they have to say.

“We’re not barbarians, we’re not like them,” she says, forcefully, shoving her finger behind her, in the police’s direction. “We’re going to listen to what they have to say. It doesn’t mean we have to accept it.”

Some in the crowd didn’t like that.

“Lady, fuck that shit,” a man yells out, with a competing megaphone. “Fuck y’all doing? Calling the manager?”

A small back and forth ensues, but the dissidents are quelled, momentarily. Still, confusion reigns. A representative is sought. A command is given for white allies to rush to the front of the barricade, they do, with enthusiasm, before the order is rescinded by someone who has assumed power, probably because of their access to a megaphone.

On the police side of things, things seem equally chaotic. Someone with authority — I can’t tell if it’s a captain or the Police Chief — is yelling “one on one,” at the woman with the megaphone. Only one of you is to come forward; more than that, and it’s a threat.

It’s at that moment that I realize that the police are terrified of us. Terrified. They are shit-scared of a group of kids. What they don’t know is that we’re just people, just folks. The thought occurs to me: do they know that if they just left us alone, nothing would happen? No riots, no burning shit. No insanity.

But then again. This is what they have been preparing for: mass uprising, social insurrection, race war. The people discovering their own power, the people realizing that they have a power equal to or greater than the power of the militarized police state. That once we stop complying, once the people withdraw their consent, their authority will be threatened, perhaps fatally.

All we are demanding, as organizer Jamaica Miles said yesterday, is what we are owed.

Maybe that is terrifying to some.

Negotiations proceed apace at the demilitarized zone roughly halfway between the barricade and the police line, but back on the homefront, dissension rears its ugly head again.

“Negotiation is what you want, lady, that’s not what we want!”

“Talking to the police isn’t doing shit!”

“Killer cops! Killer cops!”

Then: a light. an older organizer appears on the stage: a veteran organizer in this area, a leading member of Justice For Dahmeek, the organization that put together today’s earlier rally. She’s an elder of the movement, but maybe that’s a relative term. She’s not all that old, but she’s certainly older than the youth gathered here today.

“If we’re arguing with each other tonight, we not ready,” she says, a kindly, loving smile on her face. “Fuck those motherfuckers,” she says, throwing a dismissive arm behind her in the direction of the police, and fear dissipates; literally disappears before us.

“It’s important that we listen to Black leadership, but if Black leaders can’t agree, we’re not ready.” Not ready to confront the police, not ready to make a unified stand, not ready. “We have one voice. This isn’t one night. Tomorrow, we’ll be in Clifton Park, and we’ll be here in Troy. We gonna get justice.”

“To the brother who said he’s not on that peaceful shit, don’t worry, we not either,” she says.

And she’s right: there’s nothing peaceful about this. Nothing was burned, nothing was broken into. No violence occurred, unless you count the stray water bottle that was tossed over the barricade “violence”. But this wasn’t a peaceful assembly. It was a powerful one. It was two forces — the state and the people — facing off against each other, eyeing each other, flexing their muscles.

Things kind of dissipate after that. The energy of the night is sapped — not the energy of the movement. That is a slow burning candle, and there’s plenty of wax left. But tonight, the crowd thins out, folks head home.

At some point, someone, probably watching a livestream at home, has the bright idea to hand out pizza to the crowd. Some guys from Two Buttons Deep show up with Dominoes. Normalcy reestablishes itself.

Tomorrow, though. Tomorrow, we will come back.

And watch the flower bloom again.

This has been an edition of Them and Us, which is a new newsletter providing news and radical views about New York’s Capital Region, produced mainly by left journalist, Jaya Sundaresh.

If you’d like to support this work, you can by subscribing to this newsletter.

If you’d like to contribute in a more substantial way, or if you have comments, feel free to direct them towards themandusmedia@gmail.com.

We are on Facebook. We are on Twitter.

Thank you for reading.